7 Johnson Lake

Chukwuemeka Ikegwu and Mark Butler

About Johnson Lake

Johnson Lake is a secluded and relatively small alpine lake in British Columbia’s Thompson-Nicola region (Angler’s Atlas, n.d.d; Best Sun Peaks, n.d.b). It is located approximately 100 km northeast of Kamloops and takes around 70 to 90 minutes to drive there one-way (Best Sun Peaks, n.d.b). Dominating the landscape adjacent to the lake is the Samatosum Mountain peak, which provides breathtaking views of the surrounding area (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.a).

Indigenous Value

The lake rests on the traditional lands of the Simpcw First Nation (British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, n.d.a). “The Simpcwúl’ecw are part of the Secwepemc, or Shuswap Nation- one of 17 Bands who historically (and currently) lived in the Thompson River Valley” (British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, n.d.a). The Simpcw people were traditionally renowned for their hunting capabilities and would lead nomadic lifestyles that depended greatly on the seasonal climate of the region (Simpcw First Nation, n.d.). In the summer months, hunting camps were established where Simpcw people would use nets, spears, and weirs to fish, primarily for salmon. In addition to fishing, they would also hunt for wildlife in forests and fields and smoke or dry their meat for storage, which would last them well into the winter months until it was time to hunt again. Another common activity was plant harvesting, which played an integral role in procuring medicines and agricultural purposes.

Name Origin

The origin of Johnson Lake’s name is unknown as it lacks any historically valid or official verification tools to authenticate claims that attribute its name to specific nomenclature. However, it can be inferred that First Nations people had previously named the lake, but, subsequently, a settler, newcomer, or explorer (presumably of Anglo-Norman descent) in the region had renamed the lake after their surname ‘Johnson.’ This assumption is based entirely on conjecture and supposition, as no evidentiary claims support or corroborate this assertion.

Geophysical Attributes

Johnson Lake’s remarkably clear and vibrant blue-green hue is a product of water gradually seeping through its limestone rock formation from the surrounding year-round subsurface springs and winter snowpack (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b). The lake is also in a riparian zone, characterized by “direct interaction between terrestrial and aquatic habitat,” where trees grow right up to the lake’s edge (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b; Swanson et al., 1982). This type of ecological zone is very sensitive to disturbances.

There are two bodies of water comprising Johnson Lake: Little Johnson Lake, which is designated for Johnson Lake resort guests, and Big Johnson Lake, which is open to the public (Hannah, 2023). There remains a severe lack of official data for assessing Johnson Lake in its entirety. There is insufficient evidence pertaining to Little Johnson Lake, in particular, as much of the information about Johnson Lake refers to Johnson Lake and Big Johnson Lake interchangeably. This confusion renders the generation of an accurate assessment that encapsulates Little Johnson Lake extremely difficult. In addition, extensive and exhaustive research only revealed the length of Little Johnson Lake and its respective depth; however, it lacked any specification regarding its width, which makes ascertaining its surface area problematic.

For simplicity’s sake, the analysis will concentrate on Big Johnson Lake as synonymous with Johnson Lake. Johnson Lake is approximately 5 km long and 0.5 km wide, covering a total surface area of 2.5 km2 (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b). The lake is elevated at 3,800 ft and is symptomatic of its cooler water temperatures (Best Sun Peaks, n.d.b). It maintains a maximum depth of up to 200 ft with an estimated average depth of 46.9 m. The total volume of water contained within the lake is unknown, but it is roughly assessed to hold around 117.25 million cubic meters of water.

In addition, a protected narrow gravel-lined waterway (acting as a spawning channel) connects one end of Big Johnson Lake to Little Johnson Lake (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b). Every summer, Kamloops rainbow trout hatch and subsequently, the ‘fry’ travel to Big Johnson Lake using a specially built fish ladder in the spawning channel. This journey is nothing short of a magnificent spectacle that visitors can marvel at.

Recreational Activities

The Johnson Lake Resort, opened in 1952, is a quaint and private resort beside Little Johnson Lake offering visitors accommodation at one of the six self-contained cabins or one of their eight campsites that vary in size (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b). Visitors to the lake can engage in various activities during the spring, summer, and even fall seasons. However, one emphasized caveat is the zero tolerance and strict adherence to rules prohibiting the use of high-powered motorboats, jet skis, motorbikes, and ATVs (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.a). Some popular activities at Johnson Lake include fishing (fly, spin, troll), swimming, bird watching, wildlife viewing, canoeing, kayaking, hiking, mountain biking, and scuba diving.

Potential Ecological Issues

Regarded on social media as the “Caribbean of the North” (Kamloops This Week, 2015), Johnson Lake has garnered significant attention due to its isolated location, unique colour, and pristine water. This recent publicity has increased its popularity and attractiveness to many visitors seeking to marvel at the lake and capture a picture for social media.

Unfortunately, this sudden popularity has greatly increased the number of visitors coming to the lake, resulting in a massive strain on the ecosystem and interfering with the preservation of the surrounding area. The excessive increase in visitors also overloads the existing infrastructure’s capacity because the facilities, including the public camping sites and the private resort, are not meant to handle that many people at once.

This development has sparked controversy concerning overcrowding and negative environmental impacts on the delicate lake and its ecosystem that accompany increased traffic to the area (Daybreak Kamloops, 2015). A pattern of destructive behaviour has been observed with the increase in tourism, including smouldering fires left at campsites, trash (including toilet paper and feces) being scattered nearby campsites, and the creation of unsanctioned and unauthorized trails, which greatly disturb the integrity of the ecosystem.

In 2020, CBC News’ Daybreak Kamloops wrote an article regarding the recent concerns about Johnson Lake recently and interviewed people familiar with the spot before it became an overnight sensation (Daybreak Kamloops, 2020). Kamloops resident Kathleen Karpuk told CBC’s Daybreak Kamloops she was shocked by what she saw when she went to Johnson Lake for a paddle last weekend; there were dozens of tents pitched along the road outside the packed overnight campground and day-use area, new trails to the lake cut through the forest, and evidence of campfires.

CBC’s publication highlights the shameful, depraved, and abhorrent behaviour that many ecologically fragile areas are subjugated to. The unsolicited and unsanctioned activities of ignorant or arrogant visitors propagate ecosystem destruction for the sake of social media validation and show a disregard for preserving nature. Newspaper articles with eyewitness accounts and anecdotal personal testimony are unlikely to impact the policies that govern natural resources, such as Johnson Lake, and may be dismissed as hyperbole. However, we believe that placing an undeniable and relevant economic value on the lake (such as this publication strives to do) may sway the narrative towards inspiring concrete and decisive action to ensure its rights and existence are protected.

Ecosystem Services

Costanza et al. (1997) identified 17 ecosystem services of importance in their study. Every lake can concurrently supply a variety of ecosystem services; however, their exact output is determined by the physical attributes of the basin as well as the quantity, quality, and timing of water flow (Sterner et al., 2020). Johnson Lake provides a variety of significant ecosystem services that are critical for the overall health and wellbeing of the environment. Examples of the primary ecosystem services provided by Johnson Lake include

- Water provision — The lake provides potable drinking water and supplies untreated spring water to the Johnson Lake Resort (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.b).

- Recreational opportunities — As a popular recreational destination, the lake and its surroundings offer visitors opportunities to engage in various activities such as wildlife viewing, camping, and hiking (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.a).

- Climate regulation — The high elevation is responsible for cooler water temperatures, and this helps manage the local climate by providing humidification and reducing the impact of heat waves and extreme weather events (Best Sun Peaks, n.d.b).

- Habitat for wildlife — Johnson Lake is home to several fish, including rainbow trout, and other wildlife species, such as moose, deer, black bears, Canada lynx, and bald eagles (Best Sun Peaks, n.d.b).

- Carbon sequestration — Johnson Lake, sitting in a riparian zone with adjoining forested areas, including the Samatosum Mountain range, contributes to processes of carbon storage and conversion to oxygen, which are significant for reducing the effects of climate change (Johnson Lake Resort, n.d.a, n.d.b).

It is difficult to identify which of the lake’s ecosystem services is considered the least vital because they all play an important role in contributing to the region’s biodiversity. However, it is crucial to highlight that, under different conditions, the relative value of different ecosystem services can alter over time. As a result, they should all be considered precious and protected to ensure the delicate balance of human interaction and the conservation of Johnson Lake.

Valuation of Johnson Lake

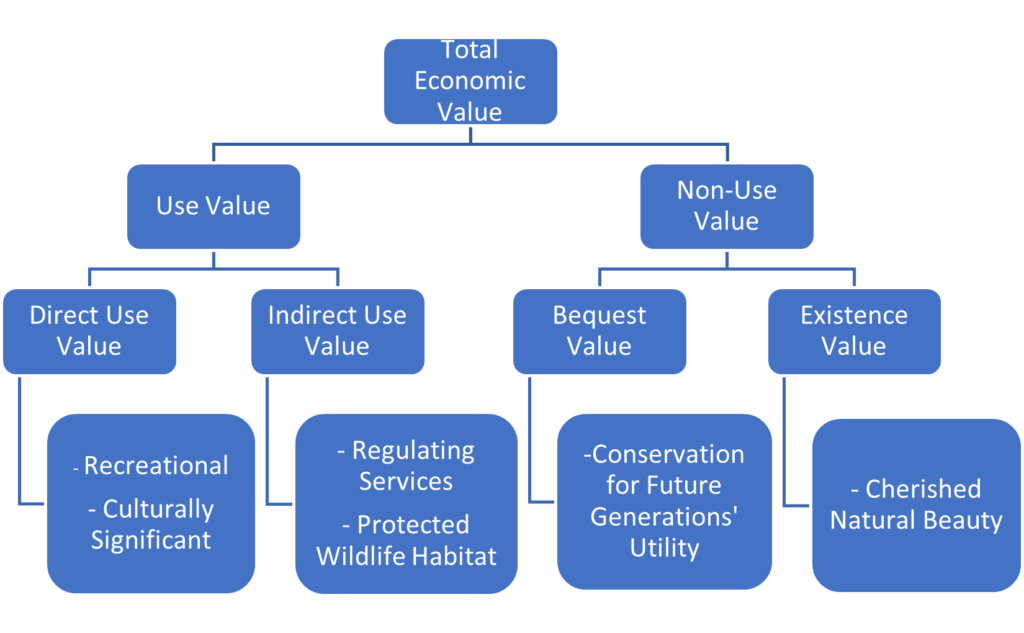

Figure 22 represents the linkages between use and non-use values in the makeup of the total economic value of Johnson Lake. Use values, including direct and indirect use values, can be attributed to both economically based production and consumption values as well as non-consumptive values where benefits are generated from interaction (Armstrong et al., 2017) with the lakes. Non-use values occur innately from nature itself, do not require interaction, and are merely speculated from its very existence or the value placed on the utility that may be extracted from future generations (Laurans et al., 2013).

Understanding these economic values is critical to making informed decisions about managing and conserving the lake for future generations. Emphasizing these traits will assist in advocating the assortment of benefits ascribed to Johnson Lake and ensuring that their social, economic, and environmental value is safeguarded.

Methodology

Policymakers deploy various valuation methods to estimate the value of ecosystem services and address losses related to ecosystem degradation. These methods include contingent valuation, choice experiment, travel cost method, hedonic pricing, and benefit transfer method (BTM). For this study, we applied BTM because it’s the most cost-effective method, and policymakers often utilize it because of constraints in time and funding (Johnston & Rosenberger, 2010). According to Plummer (2009), the BTM is a technique that estimates the overall economic value of one site by using the value of another site, known as the study site. The BTM allows you to apply previously acquired information about the cost per hectare of other lakes to Johnson Lake.

Value of Ecosystem Services

Determining a quantifiable economic value for Johnson Lake is essential for conveying the categorical importance of the ecosystem services it provides. This estimated value can be useful for policymaking in resource management, land usage extensions, and other functions that may influence the ecosystem’s biodiversity. The estimations can portray a compelling rationale for prioritizing responsible environmental stewardship and sustainability in the face of trade-offs that underpin consequential decisions and commitments for economic development and environmental conservation. Using the BTM to establish numerical benchmarks in a temporal economic assessment will reinforce Johnson Lake’s position of significance. Using the estimated values of freshwater lakes derived from the Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD) was essential to commission an appropriate and tangible estimated economic value for Johnson Lake (Brander et al., 2023). The ESVD estimates the value of ecosystem services of Canada, the UK, and the USA in International dollars per hectare per year, which can be found in Table 1.

We extrapolated the total estimated economic values of ecosystem services by ascertaining the surface area of Johnson Lake in hectares and multiplying that area by the totals in each ecosystem services category in Table 1. Then, we discounted the values accordingly. We implemented two social discount rates to determine the quantitative value of Johnson Lake as a natural asset. The first was an upper-end, but still relatively modest, social discount rate of 1.5%. The second was a very low rate of 0.1%, which accounted for the importance of Indigenous people’s valuation of water streams. We used these rates to calculate the present value of future flows based on a long-term evaluation of the lake’s ecosystem services.

Table 18 shows a summary of the value of Johnson Lake using these rates.

Table 18: Value of Johnson Lake as a Natural Asset

| Skip Table 18 | |||

| Valuation | Ecosystem Services per year (in millions of USD) | 1.5% Discount Rate (in millions of USD) | 0.1% Discount Rate (in millions of USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 19.7 | 1,313 | 19,701 |

| Median | 14.4 | 962.1 | 14,431 |

| Conservative/Modified Median | 5.8 | 392.3 | 5,885 |

In Table 18, the 1.5% discount rate used in the analysis generated a more conservative valuation, whereby the value of Johnson Lake is, on average, $1,313 million, the median valuation being $962.1 million, and the modified median valuation sitting at $392.3 million. Applying the lower-end discount rate of 0.1% resulted in higher economic values attributed to Johnson Lake for an average of $19,701 million, a median of $14,431 million, and a modified median of $5,885 million, respectively. These numbers depict an unequivocal basis for the importance of the ecosystem services hosted by Johnson Lake, without the use of hyperbole, and are part and parcel of the overall basis for the need to protect, preserve, and maintain the lake.

Concluding Remarks

Johnson Lake provides immensely valuable ecological services that benefit humans, wildlife, and the environment. However, due to the lake being in a riparian zone and recent public exposure, Johnson Lake is vulnerable and prone to environmental depredation and misuse/mistreatment, resulting in the deterioration of the lake and its surrounding areas. By emphasizing the importance of advocating for policies to protect the environment and the related services they provide, efforts can be made to assure sustainability for future generations. The valuation of Johnson Lake’s ecosystem services is significant because it helps users comprehend its economic value and, ideally, persuades policy and development considerations towards a stance emphasizing preservation. In conclusion, Johnson Lake is a treasured part of nature and one example of the immense potential of natural resources and a plethora of ecosystem services that people can experience from the lake.

Media Attributions

Figure 21: Johnson Lake Kayaking by Jessica Obando Almache (2024) is used under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Figure 22: Breakdown of the total economic value hierarchy of Johnson Lake, BC by the authors is under CC BY-NC-SA license.

References

Angler’s Atlas. (n.d.d). Johnson Lake. https://www.anglersatlas.com/place/100450/johnson-lake

Armstrong, C. W., Kahui, V., Vondolia, G. K., Aanesen, M., & Czajkowski, M. (2017). Use and non-use values in an applied bioeconomic model of fisheries and habitat connections. Marine Resource Economics, 32(4), 351–369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/693477

Best Sun Peaks. (n.d.b). Johnson Lake BC – beautiful Caribbean of the North. https://www.bestsunpeaks.com/johnson-lake.html

Brander, L. M., de Groot, R., Guisado Goñi, V., van ‘t Hoff, V., Schägner, P., Solomonides, S., McVittie, A., Eppink, F., Sposato, M., Do, L., Ghermandi, A., and Sinclair, M., Thomas, R., (2023). Ecosystem services valuation database (ESVD). Foundation for Sustainable Development and Brander Environmental Economics. https://www.esvd.net/

British Columbia Assembly of First Nations. (n.d.a). Simpcw First Nation. https://www.bcafn.ca/first-nations-bc/thompson-okanagan/simpcw-first-nation-0

Costanza, R., d’Arge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., O’Neill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., & van den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387(15), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0

Daybreak Kamloops. (2015, July 15). Johnson Lake destruction, overcrowding blamed on social media. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/johnson-lake-destruction-overcrowdingblamed-on-social-media-1.3151542

Daybreak Kamloops. (2020, August 7). COVID-19 staycation crowds blamed for misuse, damage at pristine lake in B.C.’s southern Interior. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/johnson-lake-environment-damage-camping-covid-19-overcrowding-1.5679181

Hannah. (2023, August 17). Ultimate guide to visiting Johnson Lake BC. That Adventurer. https://thatadventurer.co.uk/johnson-lake-bc/

Johnson Lake Resort. (n.d.a). Activities. https://www.johnsonlakeresort.com/activities

Johnson Lake Resort. (n.d.b). Keeping the lakes clean & clear. https://www.johnsonlakeresort.com/conservation-the-lakes

Johnston, R. J., & Rosenberger, R. S. (2010). Methods, trends and controversies in contemporary benefit transfer. Journal of Economic Surveys, 24(3), 479–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00592.x

Kamloops This Week. (2015, April 1). Local travel: Johnson Lake is the Caribbean of the north. https://archive.kamloopsthisweek.com/2015/04/01/local-travel-johnson-lake-is-the-caribbean-of-the-north/

Laurans, Y., Pascal, N., Binet, T., Brander, L., Clua, E., David, G., Rojat, D., & Seidl A. (2013). Economic valuation of ecosystem services from coral reefs in the South Pacific: Taking stock of recent experience. Journal of Environmental Management, 116, 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.11.031

Obando Almache, J. (2024). Johnson Lake kayaking [Image].

Plummer, M. L. (2009). Assessing benefit transfer for the valuation of ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1890/080091

Simpcw First Nation. (n.d.). Our history. https://www.simpcw.com/our-history.htm

Sterner, R. W., Keeler, B., Polasky, S., Poudel, R., Rhude, K., & Rogers, M. (2020). Ecosystem services of Earth’s largest freshwater lakes. Ecosystem Services, 41(101046). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.101046

Swanson, F. J., Gregory, S. V., Sedell, J. R., & Campbell, A. G. (1982). Land-water interaction: The Riparian Zone. In R. L. Edmonds (Ed.), Analysis of coniferous forest ecosystems in the Western United States. Hutchinson Ross Publishing Co.

Long Descriptions

Figure 22 Long Description: A tree diagram that breaks down the total economic value of Johnson Lake. Starting from the top, Total Economic Value is broken down into Use Value and Non-Use Value. Use Value is divided into Direct Use Value and Indirect Use Value. For Direct Use Value, examples include recreational and culturally significant. For Indirect Use Value, examples include regulating services and protected wildlife habitat. Non-Use Value is divided into Bequest Value and Existence Value. Bequest Value includes conservation for future generations’ utility, while Existence Value includes cherished natural beauty. [Return to Figure 22]